Our Research

The role of stigma and cultural barriers in accessing mental health support for postpartum depression among African, Caribbean, and Asian women in the UK.

Introduction

Postpartum depression is a mental health state that occurs after a woman has given birth and, as a consequence, feels sad, emotionless, and emotionally drained. While childbirth is often associated with positive feelings and the excitement of bringing another human being into this world, many women experience a completely different state of mind after the delivery of their baby. There are many factors contributing to postpartum depression such as financial difficulties, the lack of support from family, relationship problems with partners, genetic implications, prior mental health struggles, and socio-economic background. While many studies examine the obvious aspects of postpartum depression such as co-existing health problems, family life, and lack of support, it is important to study the cultural factors that contribute to postpartum depression to understand the level of support required by women from stigmatised societies.

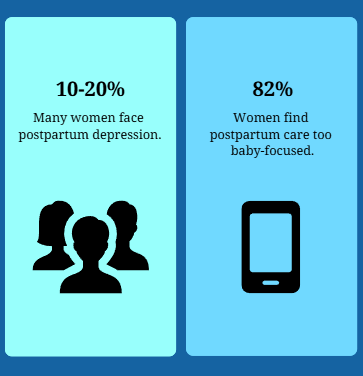

According to the World Health Organisation (2023), postpartum depression disorder affects anywhere between 10 to 20 percent of the population, which is a significantly high number. While this problem affects women from all backgrounds and countries, this study will focus on the mental health support for postpartum depression among Caribbean, African, and Asian women living in the UK. Previous research within this area explored a wide range of socio-economic factors that may be causing postpartum depression. Still, there is insufficient research focusing on treating PPD and access to health resources, which this study will examine.

Literature Review

Kozhimannil (2011) found that African, Caribbean, Afro-American and Latina women were the least prone to seek help with postpartum depression in comparison to European women. Her study focuses on the impact of low income on the access to mental health resources for mothers. The relationship between finances, cultural differences, and the cost of mental health support is evident in her study, which shows that African, Caribbean, Afro-American and Hispanic mothers coming from low-income households do not reach out for help due to a lack of money for therapy and prioritising family duties over their mental health. Another study (House et al., 2020) revealed that the disparities between mental health support access among Asian and African and European women can be related to the fact that women from African, Caribbean, and Asian backgrounds seeking help are not always offered the same treatments as other women. Such practices can lead to an increased number of women suffering from PPD and feeling doubtful about seeking professional help.

Postpartum Depression Disparities: Cultural and Systemic Barriers to Support

For this study and an accurate overview of the mental health support for women postpartum residing in the UK, we surveyed to collect relevant data about women’s experiences after childbirth. The survey was designed to collect both qualitative and quantitative data to provide a thorough insight into the overall experience of accessing mental health support for postpartum depression among women living in the United Kingdom.

More specifically, the survey asked women about the level of support they have received from healthcare providers and their close ones, the feelings they were experiencing when coming home with their child after giving birth, whether they sought mental health support during this time, and whether they would have felt more comfortable seeking support in a different environment among other key questions. We also asked participants to include any suggestions on what sort of support or services they would like to be offered during the next pregnancy and postpartum period to gain a better understanding of what the current healthcare system is lacking. Apart from practice-based research and creating a survey, we base our findings and key points on existing academic research and statistics from various mental health organisations, the World Health Organisation, journal articles, and other credible resources available online.

Why Women Aren’t Getting the Help They Need

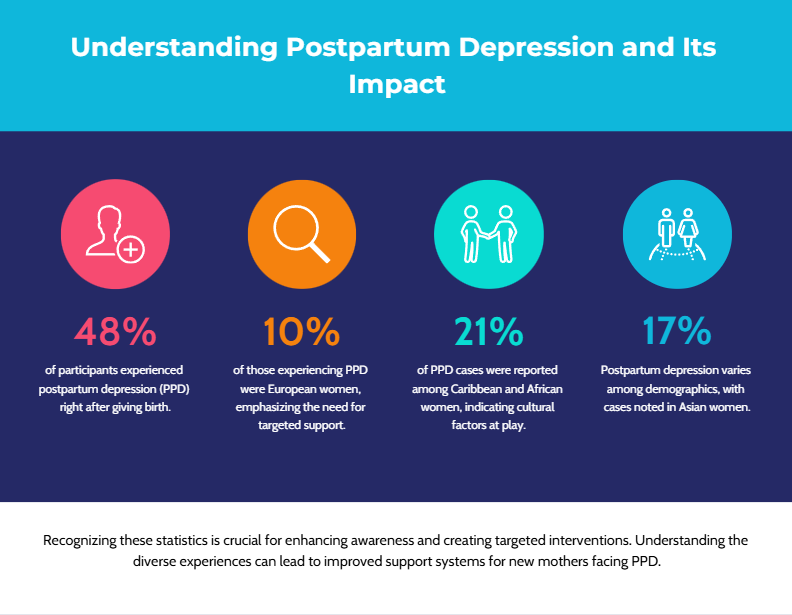

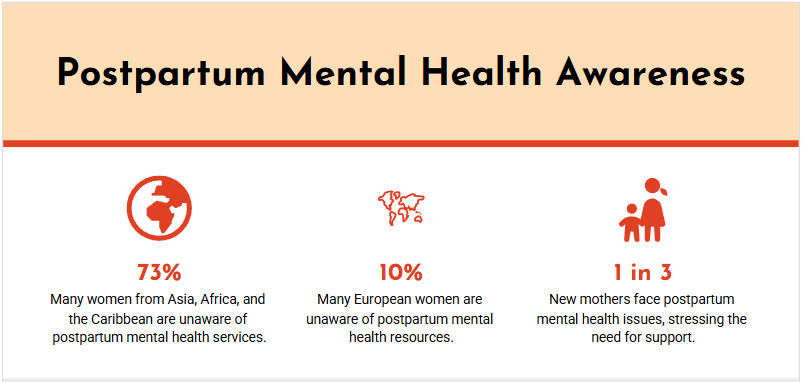

Our study based on fifty participants found that a lot of women experienced feelings like sadness, disappointment, and burnout immediately after giving birth or in the first few days postpartum. 48% of participants expressed that they experienced postpartum depression soon after coming home from the hospital, out of which 21% were African and Caribbean women and 17% were Asian women. Overall, we noted the significant disparity between the number of European women affected by postpartum depression immediately after giving birth and those of minority backgrounds based on this specific survey.

Women who come from different cultures and/or are migrants in the UK may feel isolated and misunderstood by society due to different ideologies but also different environments and communication patterns among other factors. Schmied (et al., 2017) mentions in her study how migrant women may feel lost in a new country and not have relatives to reach out to or not know the healthcare system in the UK, which puts them at a disadvantage as opposed to British women. In our study, 73% of women did not know about the services available to them during postpartum, out of which only 10% of women were European. The study shows that women coming from underrepresented groups do not have enough knowledge and resources to know where to ask for help with their mental health postpartum, making it difficult to access support from professional practitioners.

A striking 82% of women mentioned that the postpartum support from healthcare professionals was baby-centred and did not take into consideration mums’ physical and mental fitness with some adding they wish they had been given more support as new mothers rather than being provided with support only for their newborns. Gopalan (et al., 2022) discussed in her study how the healthcare system neglects to support women during their pregnancy, which increases their chances of developing postpartum depression. According to her findings, there are far fewer prenatal mental health screenings than, for example, diabetes screenings. Doctors are focused on the physical well-being of future mums and do not put enough focus on their mental health. Gopalan’s study also examines how systematic racism in the healthcare sector puts African, Caribbean, and Asian women at a disadvantage by not providing them with the same access to treatments as other women and being universal without cultural adjustments. Based on our findings, we have noticed a pattern of European women having less severe PPD as opposed to other women, which seems to prove Gopalan’s key points.

In our research, we have noticed that Asian, African, and Caribbean women often feel as though they are treated with less respect than other women, but there is not enough evidence to support those claims. However, the fact that both European and non-European women feel that the healthcare system does not support them is alarming.

Addressing Gaps in Postpartum Mental Health Support

The key issue we noted is that regardless of ethnicity, all women felt like they were not fully supported during the postpartum period. However, the level of support provided to women varied based on the person. From the answers, we could not identify whether women coming from underrepresented groups were treated less favourably by healthcare providers but we determined that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach followed by the healthcare system. The care provided to mothers is more of a gamble and random selection of resources rather than a structured system in place. In his study, Skoog (et al., 2022) discussed various screening methods for postpartum depression disorder, which supports our finding that there is a clear lack of structure in helping mothers suffering from PPD. He also mentions how healthcare professionals find it challenging to identify PPD in African, Caribbean, and Asian women due to their lack of disclosure and cultural barriers surrounding mental health.

This research showed that postpartum depression is a common condition in the United Kingdom with 100% of participants admitting to showing negative feelings during postpartum and 48% experiencing those feelings immediately after giving birth. Such striking numbers cannot be ignored by the healthcare professionals. With the rising number of mothers suffering from postpartum depression disorder, the NHS system must act upon those and other research findings to provide better support and tackle this issue. While we were able to identify the key issues relating to the lack of culturally-centred support for minority women, this research has its limitations. We suggest discovering more research conducted by Prady (et al., 2018), Hadfield (et al., 2019), Rosenfield (2007), and other scholars to better understand the gaps in treatments available to women suffering from postpartum depression as well as conducting individual research to compare those findings and shed new light on the support required by women postpartum.

Please, be advised that below is a short version of our research. For full research and insights, please contact us directly.

Email: info@weholdahand.com

References:

- Amankwaa L. (2005), ‘Maternal Postpartum Role Collapse as a Theory of Postpartum Depression’, The Qualitative Report, 10(1), pp. 21-38.

- Babatunde T. and Moreno-Leguizamon C. (2012), ‘Daily and Cultural Issues of Postnatal Depression in African Women Immigrants in South East London: Tips for Health Professionals’, Nursing Research and Practice.

- Bina R. (2008), ‘The Impact of Cultural Factors Upon Postpartum Depression: A Literature Review’, Health Care for Women International, 29(6), pp. 568-592.

- Bonas S. and Ockleford E. (2012), ‘Barriers to accessing mental health services for postnatal depression in the UK: a literature review’, University of Leicester.

- Brockley B. (2023), ‘Stratified Post-Reproduction: An Analysis of Black Women’s Barriers to Postpartum Depression Treatment’, Undergraduate Journal of Public Health, 7(2023).

- Claxton M. (2021), ‘An Investigation into the Relationship between Obstetric Racism and Postpartum Depression in Black Women’, University Honors Theses, Paper 1159.

- DiPetrillo B. (2022), ‘Postpartum Social Support Experiences of Black Mothers with Depression during COVID’, Dissertation, Georgia State University.

- Gopalan P. et al., (2022), ‘Postpartum Depression—Identifying Risk and Access to Intervention’, Reproductive Psychiatry and Women’s Health, vol. 24, pp. 889-896.

- Goyal M. et al., (2014), ‘Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), pp. 357-368.

- Hadfield H. et al., (2019), ‘Psychological Therapy for Postnatal Depression in UK Primary Care Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Investigation Using Framework Analysis’, Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 18, pp. 3519-3532.

- Harris E. et al., (2024), ‘Current policy and practice for the identification, management, and treatment of postpartum anxiety in the United Kingdom: a focus group study’, BMC Psychiatry, 24(680).

- Hassani K. et al., (2015), ‘Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 70, pp. 67-82.

- House T. et al., (2020), ‘Mommy Meltdown: Understanding Racial Differences Between Black and White Women in Attitudes About Postpartum Depression and Treatment Modalities’, J Clin Gynecol Obstet, 9(3), pp. 37-42.

- Jidong D. et al., (2022), ‘Culturally adapted psychological intervention for treating maternal depression in British mothers of African and Caribbean origin: A randomized controlled feasibility trial’, Clinical Psychology Psychotherapy, 30(3), pp. 548-565.

- Kozhimannil K. (2011), ‘Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Postpartum Depression Care Among Low-Income Women’, Psychiatric Services, 62(6).

- Liu S. et al. (2022), ‘Assessing the Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Postpartum Depression Using Population-Level Hospital Discharge Data: Longitudinal Retrospective Study’, JMIR Pediatr Parent, 5(4).

- MacLellan J. et al., (2022), ‘Black, Asian and minority ethnic women's experiences of maternity services in the UK: A qualitative evidence synthesis’, JAN Leading Global Nursing Research, 78(7), pp. 2175-2190.

- Prady S. et al., (2018), ‘Evaluation of ethnic disparities in detection of depression and anxiety in primary care during the maternal period: Combined analysis of routine and cohort data’, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(5).

- Rosenfield A. (2007), New Research on Postpartum Depression, Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers.

- Schmied V. et al., (2017), ‘Migrant women’s experiences, meanings and ways of dealing with postnatal depression: A meta-ethnographic study’, PLOS One.

- Skoog M. et al., (2022), ‘Health care professionals’ experiences of screening immigrant mothers for postpartum depression–a qualitative systematic review’, PLOS One.

- Stuart A. (2024), ‘Unseen, Unheard, and Unknown: Postpartum Depression Among Women of Color’, Wake Forest University.

- World Health Organisation (2024), Mental Health, Brain Health and Substance Use, Available at: Mental Health, Brain Health and Substance Use (Accessed: 29/12/2024).